I am still experimenting with how Space Y will cover science, space and SpaceX among other topics, so bear with me. This article lives at the intersection of news and pop-space studies.

Hot Jupiters are a class of gas giant exoplanets that are inferred to be physically similar to Jupiter but that have very short orbital periods. There are many types of planets that are actually pretty common that aren’t present in our own home solar system.

Our understanding of the cosmos however is improving in leaps and bounds.

This is fascinating to me though is a bit like the clickbait of space news. Mysteries of 'hot Jupiters' unravelled: Gas giants that orbit close to their star are hot enough to vaporize TITANIUM during the day — but hundreds of degrees cooler at night, study finds.

Hot Jupiters are gas giants that orbit close to their star, typically in less than 10 days.

Because of this proximity, the irradiation from the star heats the planet to several hundred to a few thousand degrees Celsius.

While the Hubble Space Telescope celebrates 32 years in orbit, like a fine wine, it has only gotten better with age as it continues to study the Universe and teach us more about our place in the cosmos.

Sunburn by Ultra Violet Rays

In two new papers, teams of Hubble astronomers are reporting on bizarre weather conditions on these sizzling worlds. It's raining vaporized rock on one planet, and another one has its upper atmosphere getting hotter rather than cooler because it is being "sunburned" by intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation from its star.

This research goes beyond simply finding weird and quirky planet atmospheres. Studying extreme weather gives astronomers better insights into the diversity, complexity, and exotic chemistry taking place in far-flung worlds across our galaxy.

In one of the largest ever surveys of exoplanet atmospheres ever undertaken, UCL researchers discovered that the night and day sides of hot Jupiters are very different.

In two papers published in Nature and Astrophysical Journal Letters, teams of Hubble astronomers are reporting on bizarre weather conditions on two sizzling worlds known as hot Jupiters, WASP-178b and KELT-20b.

During the day, they scorch in temperatures between 1500K (2240°F) and 3000K (4940°F) — hot enough to vaporise most metals, including titanium — but at night temperatures plunge by hundreds of degrees Fahrenheit.

On average the researchers found a 1000K difference in temperature between night and day.

Just imagine all the weird Jupiters out there.

Amongst other findings, the team found that the presence of metal oxides and hydrides in the hottest exoplanet atmospheres was clearly correlated with the atmospheres’ being thermally inverted.

“We still don’t have a good understanding of weather in different planetary environments,” said David Sing of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and co-author on both studies.

These Hot Jupiters are rare, but not entirely uncommon either.

Of the almost 5,000 known exoplanets, more than 300 are such hot Jupiters.

That’s still 6% of all known exoplanets. Not bad for the weird ones!

The field of exoplanet science has long since shifted its focus from just detection onto characterization, although characterization remains extremely challenging.

It’s truly hard to imagine:

In a paper in the April 7 journal Nature, astronomers describe Hubble observations of WASP-178b, located about 1,300 light-years away. On the daytime side the atmosphere is cloudless, and is enriched in silicon monoxide gas. Because one side of the planet permanently faces its star, the torrid atmosphere whips around to the nighttime side at super-hurricane speeds exceeding 2,000 miles per hour.

Definition of a Hot Jupiter

Exoplanets known as hot Jupiters are exactly what their name implies, as they are planets physically similar to Jupiter but instead orbit extremely close to their parent star, often taking only a few days to complete one orbit. As is the case with WASP-178b and KELT-20b, most hot Jupiters endure searing temperatures above 1650°C (3000°F). This is hot enough to vaporize most metals, including titanium, as hot Jupiters possess the hottest planetary atmospheres ever seen. Another unique feature about hot Jupiters is that despite them not existing in our solar system they are quite common in the galaxy, as about one in 10 stars are currently estimated to have a hot Jupiter.

By using a large sample of exoplanets and analyzing an extremely large amount of data, the researchers said the were able to determine trends and resolve questions that smaller studies have been unable to conclusively answer over many years. The more we understand about our Galaxy, the more we’ll understand about the Universe and its history. We’re all connected.

The researchers also found that some planets had less water than expected, suggesting they formed in a different way to the more water-abundant planets, while they detected more metals than predicted by models, meaning that those planets likely formed differently from what was previously thought.

The researchers said a better understanding of exoplanets will help to resolve questions about the evolution of our own solar system.

With the recent launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, it’s a passing of the torch but Hubble still has a lot of insights left to show.

With the help of A.I. and quantum computing, we’ll be able to map our galaxy and model the Universe like never before. This new work, led by researchers based at University College London (UCL), used the largest amount of archival data ever examined in a single exoplanet atmosphere survey to analyze the atmospheres of 25 exoplanets.

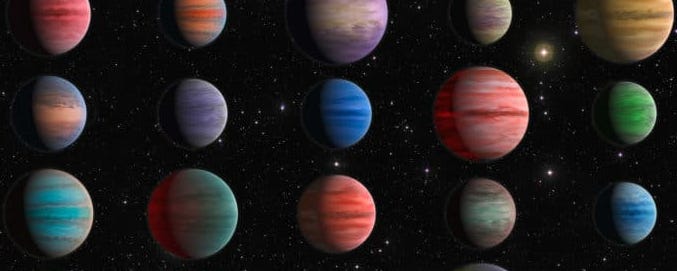

Archival observations of 25 hot Jupiters by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have been analysed by an international team of astronomers, enabling them to answer five open questions important to our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres. Amongst other findings, the team found that the presence of metal oxides and hydrides in the hottest exoplanet atmospheres was clearly correlated with the atmospheres' being thermally inverted. Credit: ESA/Hubble, N. Bartmann

That’s pretty beautiful. So is our knowledge gained in astronomy and new studies.